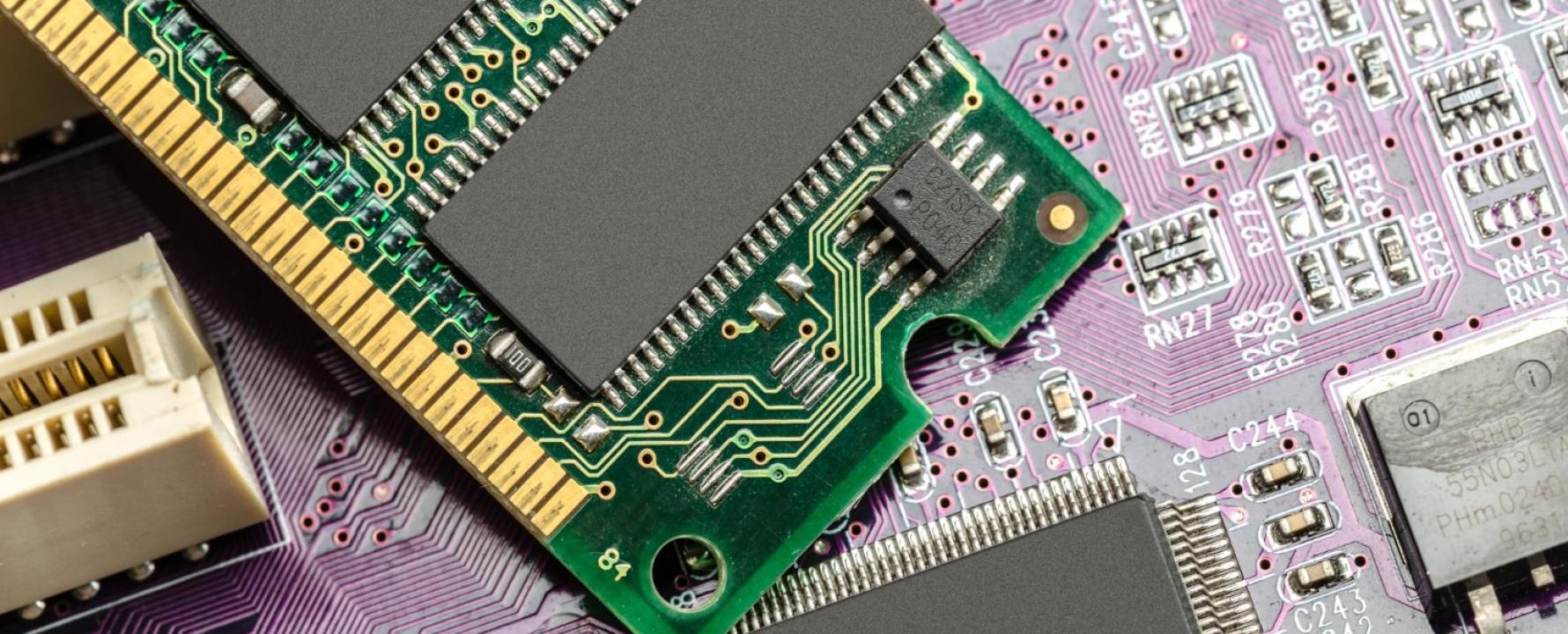

Global headlines over the past few years have repeatedly highlighted a growing strain on the supply of electronic components, and memory chips have emerged as one of the most critical pressure points. From smartphones and laptops to cars and industrial machinery, modern technology depends heavily on reliable access to different forms of memory. When that access becomes limited, the effects ripple far beyond the factories where the chips are made.

Memory shortages are closely tied to the complexity of global supply chains. Producing advanced memory chips requires highly specialized fabrication plants, massive capital investment, and a small number of companies with the technical expertise to operate at scale. When demand surges suddenly, as it did during the rapid shift to remote work and digital services, supply cannot adjust quickly. Natural disasters, geopolitical tensions, and public health crises further amplify these vulnerabilities by disrupting production or transportation at key moments.

The consequences of memory scarcity are felt most immediately by manufacturers of consumer electronics. Companies are forced to delay product launches, reduce output, or redesign devices around less optimal components. These adjustments often lead to higher prices for consumers, as limited supply meets sustained or growing demand. In some cases, manufacturers prioritize premium products, leaving lower-cost devices harder to find and widening the digital divide between different segments of society.

Beyond consumer markets, the shortage of memory chips has serious implications for industries that are not traditionally associated with electronics. Automotive production has been repeatedly slowed because modern vehicles rely on dozens of memory-equipped control units. Medical equipment, renewable energy systems, and telecommunications infrastructure also depend on stable memory supplies, meaning that shortages can indirectly affect public health, environmental goals, and economic development.

Another important dimension of the problem lies in strategic dependence. Many countries rely heavily on foreign suppliers for advanced memory technologies, raising concerns about national security and economic resilience. As a result, governments have begun to view memory production not just as a commercial activity but as a strategic asset. Incentives for domestic manufacturing, investments in research, and efforts to diversify supply sources are becoming more common, although these measures take years to produce tangible results.

Looking ahead, the memory shortage highlights a broader lesson about the fragility of highly optimized global systems. Efficiency has long been prioritized over resilience, leaving little margin for error when unexpected shocks occur. While new fabrication plants and technological innovations may eventually ease supply constraints, demand for memory continues to grow alongside trends such as artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and the Internet of Things.

The challenge, therefore, is not simply to solve a temporary shortage but to rethink how critical technologies are produced and distributed. Addressing memory scarcity requires cooperation between industry, governments, and researchers to balance innovation, accessibility, and stability. Without such efforts, the problem risks becoming a recurring feature of the digital age rather than an exception driven by extraordinary circumstances.